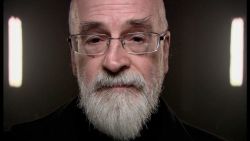

Last night, the Incredible Dement shocked the nation. Appearing on BBC2, armed with only a Euro-Rover ticket and a large hat, he toured the Continent, boldly seeking out destinations where others fear to tread. Everywhere he went, it was either raining or snowing, for these were the lands that God forgot. Soon it became apparent that, when the ID was on the road, all roads led, not to sun and the Eternal City, but to snow, and an another altogether different type of Eternity. They led to Zurich, to a dapper blue house tucked away on an industrial estate – a planning requirement, you understand – where a Mr Peter Smedley, late of the canning concern, was about to do to himself what his family had spent decades doing to peas. The only difference was that Smedley would emerge not in a can, but an urn. He had come to Dignitas, to die.

Last night, the Incredible Dement shocked the nation. Appearing on BBC2, armed with only a Euro-Rover ticket and a large hat, he toured the Continent, boldly seeking out destinations where others fear to tread. Everywhere he went, it was either raining or snowing, for these were the lands that God forgot. Soon it became apparent that, when the ID was on the road, all roads led, not to sun and the Eternal City, but to snow, and an another altogether different type of Eternity. They led to Zurich, to a dapper blue house tucked away on an industrial estate – a planning requirement, you understand – where a Mr Peter Smedley, late of the canning concern, was about to do to himself what his family had spent decades doing to peas. The only difference was that Smedley would emerge not in a can, but an urn. He had come to Dignitas, to die.

Outside, it was snowing. Mr Smedley approached his canning experience with a light Scott of the Antarctic touch. One expected him at any moment to say that he was just going outside, and might be some time. But it was not to be that way. In the cold light of the camera, Smedley downed his canning draught. Outside, it continued to snow. Inside, he exchanged light but tender words of comfort with his wife. Then he coughed, groaned, called for water, groaned again, cleared his throat, snorted, snored, and died. Just like that. The ID announced ‘a result’, and even had a good word for the snow, it being the ‘right kind’ of snow, before declaring Smedley a hero, the bravest man he had ever met. That is as may be. Certainly, Smedley showed courage and fortitude. But in Dr No’s eyes, the real hero, or rather heroine, was the Lady from Rhodesia, Smedley’s wife. It was her courage, her fortitude, and her dignity that was outstanding, so much so that it made the hardened Dr No want to weep.

Now, this programme was well made, even if it was barely one stop short of an advertorial for Dignitas and, more generally, assisted suicide. Many column inches have already been written about it, and no doubt many more have yet to come, focusing on the merits or otherwise of broadcasting footage of real death (Dr No is of the view that it was right to air it), and on the neo-sacred right to self-determination for those of sound mind and settled intent (and here Dr No finds that in the abstraction of the debating chamber, this right, taken on its own, is unassailable). So, instead, Dr No is going to consider two other, and to his eyes neglected but important, related matters, which the film did touch on, but only glancingly: the mindset of those who choose to die, and the effect of their actions on those they leave behind.

The fact remains that, however much one may wrap it in Dignitas snow, the act of suicide is at its root an aggressive act: the wilful termination of a human life. But aggression is a strange thing: it doesn’t have to be violent and active; instead, it can at times be quiet and passive – so called passive-aggression, such that the passive-aggressive individual is as a ‘snowball with rocks inside’: outwardly perhaps fluffy, but inwardly certainly barbed. And, in a discomforting way, sentient, planned open assisted suicide is the ultimate act of passive-aggression: the ultimate ‘f*ck you!’ – however gently and politely it is said.

There was a telling moment in the programme, towards Smedley’s end, when his wife offered him chocolates, ostensibly to sweeten the bitter draught to come. But, it seemed to Dr No, there was something else going on: a last but one chance for a loving wife to give something to the man she loved; and so it was as much about her being able to give, and him being able to receive. But he didn’t. ‘I don’t think it’ll matter’ he said, as he looked away, and the body language said it all. Had he had the grace to accept the – albeit macabre – gift, not for its purpose, but for its symbolism, Dr No would have felt less awkward.

Dr No suspects he was not alone in wondering about the darker motives of the two men filmed in their determination to die. Indeed – to give it its due, there were hints of this question in the programme, notably in the asides and glances of the ID’s assistant, Rob, as there were too on the related matter of the effect of suicide on those who are left behind. For it is they who are the ones who have to live daily with the history of willed death: and, as John Donne said, no man is an island, entire of itself…

We may be able to satisfy ourselves of the right to self-determination in the abstract isolation of the debating chamber. But can we do so so easily in the real world, where the wider ramifications of the ultimate act of passive-aggression cast their ripples in ever deepening circles?

I think there is world of difference between poor care and early withdrawal of fluids to hasten a death, and the entirely active and voluntary taking of a potion by someone who is wholly in control of the propcess and can stop at any time, as in the dignitas process. I am in social care on the fringes of medical care, and despite being reluctant to think that non voluntary euthaniasia would not happen in the NHS, I have seen enough worrying signs to think it might be happening. But even if it is, that should not prevent people making a decision to avoid pointless drawn out suffering, as in MND and some kinds of cancer. I saw the Pratchett programee and I too say ‘f*ck the bishop’, who seems to think that suffering of other people is ok so that people like him can feel good about themselves for being so caring (push off, priest, and pass the barbiturates, thanks). It is not so long ago that the Catholic church was against pain relief in childbirth. I have to say the same to the vociferous lady on that programme whose paranoia that everyone not in a wheelchair wants to see her dead aparently means she is quite happy to see other people suffer in ways that would get a pet owner prosecuted.

The idea that we should ask our loved ones for permission to go seems to me flawed on various levels. The only acceptable response is ‘ no we dont want you to go’, any other is socially unacceptable as people fear the disapproval of those who see plots everywhere, or to risk the person asking you then wondering if it is really that you would prefer to inherit sooner than later. AFter all few family relationships are pure and unambiguous. The only acceptable principle is that the individual is free to choose, yes by all means have a process whereby it is established as far as possible that the individual is not being pressurised, and then leave the choice to them. We may love our parents, children and spouses but we do not own them and we have to espect their choices. It is better that such decisions are for the person concerned alone.

As for doctors who would not want to get involved, fine, it should be entirely outside the health system so that there can be no possible criticisms around getting rid of expensive bed blockers etc. AFter all it does not take a doctor to hand someone a glass of medicine.

I found the programme very moving and sad, but ultimately was happy for Mr Smedley that he was able to avoid the worst that MND can do. His wife was extraordinarly brave, of course she did not want him to go but she could at least remember him as a dignified man, still handsome and in control of his destiny as he always had been. No priest or disabled lobbyist had the right to insist that he suffer to protect their outdated role or exaggerated sensibilities

Anonymous – thanks for a very thoughtful comment.

A crucial thing here, it seems to Dr No, is to be clear about the different types of ‘assisted death’, and not to blur the boundaries. Smedley, for example, was a clear case of suicide (albeit assisted) by a person of sound mind, and settled intent. Whatever one’s own personal views on the matter, society can and does accept that such an individual can determine their own fate; and so be it. That’s why we decriminalised suicide.

Today’s news includes that of a court hearing over ‘M’ – a woman said to be in a ‘minimally conscious state’ – on whether to end her life support. Here we are talking about passive involuntary (M cannot (refuse) consent) euthanasia. The ‘minimally conscious state’ cuts both ways: if she is sensible, and in pain, is that not reason to allow the end her life, to ‘let nature take its course’, and ‘not strive officiously to keep alive’? Or is the fact she is sensible (however minimal the degree) an absolute reason not to bring about the end of her life?

The ‘loved ones’ question does indeed lie at the heart of things too (and since we are calling them ‘loved ones’, who is it that loves who, and what does that love really really mean?). As you observe, few family relationships are pure and unambiguous. One of Dr No’s concerns is that any legal process intended to tease out the nuances is simply far far too crude and clumsy to be able to achieve that. How, for example, do you tease out an active choice to volunteer for euthanasia that arises only because the option is there? Or the ‘noble’ parent who doesn’t want to die, but agrees to it ‘to help their children’, and who steadfastly lies about their own true wishes.

Absolutely agree the executioners should be outside the health system. Nor do you need to be a doctor to be able to do it – all the necessary knowledge and skills could be taught on a two day course.

And Dr No thinks most reasonable people agree that religious zealots have no business whatsoever forcing their views onto others when they are not wanted.

Dr No, like you, and indeed as he has said before, but it bears repeating, was powerfully struck by the courage and composure of Mrs Smedley. If such a film can have a hero(ine), it was surely her. Dr No thinks we will learn far more from her than we ever will from the Incredible Dement (notwithstanding that without the ID, the program may not have happened), and what he startlingly called ‘a result’. To Dr No, it sounded as if a toddler had at last done what he was supposed to do.